The possible healing properties of our poop.

We are always looking for innovative new treatments, from immunotherapy to gene therapy to novel antibiotics. But what if we had innovative new treatments inside our own body, namely our gut bacteria?

What if some people’s gut bacteria could be used for treating other people’s diseases?

It has happened in the past.

The past and present use of people’s microbiome (a sophisticated name for bugs in people’s poop).

In the 4th century in China, medical doctor Ge Hong created a new treatment for diarrhea. It was called “yellow soup” and was a broth made with… not lemons, not yellow bell peppers, but the poop of a healthy person.

I can imagine you, reader, grimacing. Yet, this “yellow soup” worked very well in treating diarrhea.

More recently, when people are exposed to long antibiotic treatments, not only are the culprit bugs destroyed, but all their good bacteria are destroyed too. As a result, some people’s guts are colonized by a very-difficult-to-treat bug called Clostridium Difficile (C. Diff.) and despite additional antibiotic treatments, these patients sometimes develop recurrent C. Diff. infections.

Since no other treatment can kill these recurrent infections all of the time, some physicians try to use healthy people’s poop, sometimes using the sexual partner’s poop to treat the infected person (used as an enema). And—surprise!—the partner’s poop often cures the infected person.

Dr. Jessica Allegreti from Harvard University mentions in Harvard Health Publishing that Fecal Microbiota Transplants (FMT) have a cure rate of 80 to 90 percent with very often only a single treatment in cases of recurrent C. Diff. infections.

How FMTs work their magic isn’t yet explained, but one theory is that “healthy” bugs in our guts may secrete bactericidal compounds that kill C. Diff. Another theory postulates that when healthy bugs are restored through a transplant, they outcompete C. Diff. for nutrients.

But what if FMTs (and the bugs contained in people’s poop) could be used to treat diseases other than C. Diff. infections?

What if FMTs could be used to treat Crohn’s disease or recurrent urinary tract infections? What if FMTs could treat mental illness, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, autism, and even obesity? What if FMTs could work against cancer?

What could be the future use of people’s microbiome (contained in people’s poop)?

At the beginning of December this year, my husband and I interviewed Dr. Sabine Hazan, gastroenterologist, founder, and CEO of Progenabiome in Ventura, California, and Dr. Brad Barrows, the medical director of the company. Dr. Hazan conducts research and leads clinical trials on the microbiome and FMTs.

Dr. Hazan has done 150 clinical trials in the last 15 years. She explained that we have in our gut up to 100 trillion microbes and that there are more than 150,000 species of them—some well-known, others not so well-known.

Dr. Hazan’s theory is that, just like Penicillin was discovered from the growth of mold, all gut bacteria, gut fungi, and viruses might have properties that have yet to be discovered.

She is currently analyzing the gut microbiome of people with chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic constipation, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, recurrent urinary tract infections, psoriasis, Lyme’s disease, Alzheimers’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, autism, colorectal cancer, obesity, and several other conditions. In doing so, Dr. Hazan is discovering that patients with certain diseases have a very different gut microbiome than people without any disease.

But first let’s take a look at what a microbiome looks like, from Dr. Hazan’s point of view:

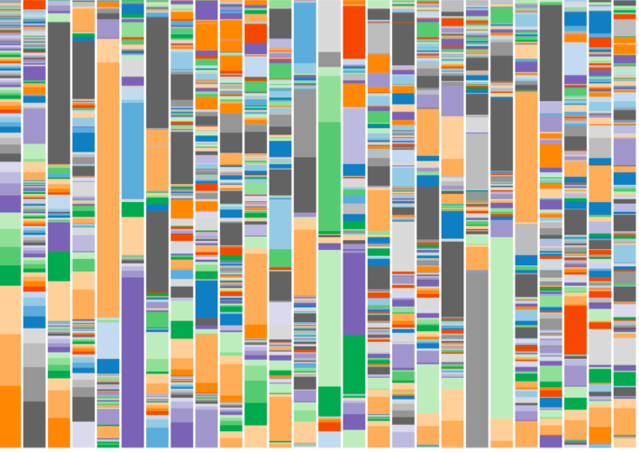

Below is a chart that shows the microbiome of 26 randomly selected individuals. In the chart, each column represents a different individual and each color represents a different species of bug. See how complex every microbiome is?

Now let’s look at families.

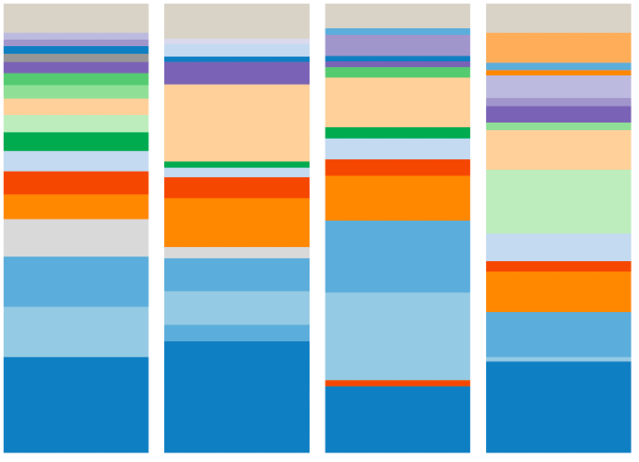

Below is the microbiome of one family:

See how the colors are kind of similar between father, mother and the two children? This means they have the same species of bugs in their guts.

Why is that?

Could it be that they are genetically related? But what about the mother and father who are not genetically related? Could it be because they kiss and have sex? Could it be because they eat the same kind of food or because they live in the same house?

All of these possibilities are likely.

Now compare the above family microbiome with the family microbiome below:

This second family has a very different microbiome than the first, which means that they have very different sets of bugs in their guts.

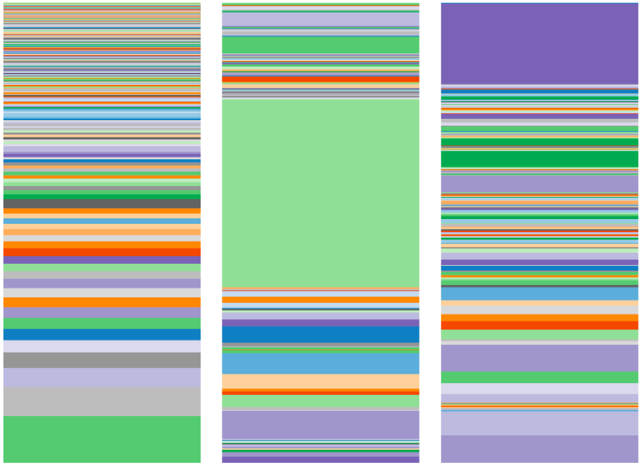

In this second family—mother, daughter 1 and daughter 2‚ one of the daughters has autism. Can you guess, just by looking at the microbiome, which one has autism?

It is the one in the middle, daughter 1.

Do you notice how different the microbiome of daughter 1 is from the rest of the family? It seems that it has too much of a certain bacteria (the one in green in the middle) and misses a lot of variety of gut bacteria, one of them being Bifidobacter.

Moreover, there is less diversity (number of different organisms in daughter 1) indicating that her microbiome is much less balanced than that of her mother or sister.

What is Dr. Hazan’s plan for the future?

Dr. Hazan’s plan is to understand the role of the microbiome in diseases and to use her findings to help her colleagues perfect the area of fecal transplant. Most importantly, she wants to shed some light on the mechanism of why fecal transplant helps improve a disease or cures Clostridium Difficile.

Dr. Hazan doesn’t believe in one pill fits everyone, nor should a probiotic fit everyone. She believes in precision medicine and individuality as well as the need to remain diversified.

“The one thing we learned from the microbiome analysis is that a healthy microbiome is one that is diverse in its microbial composition,” Dr. Hazan says.

She hopes to work with the FDA to organize a trial on autistic children using the data she gathered from microbiome analysis.

Has Dr. Hazan seen any positive results for any diseases other than Clostridium Difficile infections?

Yes, she has.

Through the mentorship of Dr. Thomas Borody, a leader in fecal transplantation, Dr. Hazan is applying methods and protocols to use FMT in a clinical trial on patients with Crohn’s disease, transplanting them with the microbiome of healthy individuals. Her results will be published soon. She has also seen improvement in one case of Alzheimer’s dementia and one case of chronic urinary tract infection.

Other physicians have had some great results too.

Dr. Moayyedi from McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, performed Fecal Microbiota Transplantations on 38 patients suffering from ulcerative colitis. Nine of Moayyedi’s patients went into remission and were able to stop all treatments (the results were published in the Journal of Gastro-Enterology in 2015).

Dr. Johnsen from Harstad University Hospital in Norway performed Fecal Microbiota Transplantations on patients suffering from Irritable Bowel Disease (IBS) and had 65 percent of patients improved—much better than placebo (these results were published in the Lancet in 2018).

So, could FMTs be the new treatment of choice for many diseases in the future?

We don’t know yet, but as Dr. Thomas Borody says: “It takes courage and years of perseverance to change paradigms.” Dr. Borody is presently working on a protocol on FMT and Parkinson’s disease.

We need more clinical trials on larger samples of patients.

The key will be to find the right Fecal Microbiota Transplant donor to treat each condition and to better assess the risks versus benefits of Fecal Transplant in the future.

In the meantime, here are more questions you may have about FMTs:

How are FMTs done?

Some people put the FMT in capsules to be taken orally, but stomach and bile acids might destroy the therapeutic microbiota if taken this way. Thus, gastroenterologists like to transplant gut bacteria via enemas or place them directly near the caecum via a colonoscopy.

How risky are FMTs?

We don’t know yet. All that we know is that the risks are not zero.

One person died after an FMT in 2019, but that individual had leukemia and a severely weakened immune system, and the donor had E. Coli bacteria that were resistant to antibiotics.

Since then, donors have been better selected.

Can FMTs reverse obesity?

Can poop be taken from a slim person and placed in the colon of an obese person so that the microbiota of the slim person take over?

Well, the answer is yes… in rats. Maria Guirro and colleague from Rovira University in Spain (the study was published in PLoS One 2019) showed that transplanting gut bacteria from lean rats to obese rats created a change in the obese rats gut bacteria, making the obese rats’ gut bacteria similar to the ones from the lean rats and thus less able to harvest energy from food.

Clinical trials with humans are starting (see in references below).

What can we take away from all this?

One thing is for sure: Depending on what we eat, drink and how much stress we have in our life, our microbiome changes and those changes can trigger diseases.

An example is that stress makes our stomach, liver, and gallbladder secrete more acid, and those acids will kill a lot of our good bacteria, creating an imbalance in our gut flora. On the other hand, eating yogurt will provide us with good bacteria, but too much sugar in our diet will create a growth of bad bacteria, creating another kind of imbalance and triggering other diseases.

So, let’s be aware that we are not alone in our bodies. We are the host of trillions of friends living in our gut that help us remain healthy. Let’s be good hosts and keep our microbiome balanced by eating less processed foods, less sugar and having less stress in our life.

Because after all, the future might really be in our poop… no sh*t!